How To Research Your Landlord For Free

A Guide to Strategic Corporate Research for Los Angeles Tenants

What is this guide?

Dear User,

This guide is designed to assist tenants in Los Angeles in using publicly available resources to investigate their landlord. I created it drawing on nearly a decade of experience in conducting research on landlords for Strategic Actions for a Just Economy, Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, the Debt Collective, and various other organizations to serve the needs of tenants wanting to do this research themselves.

By following the guide a tenant should get a good understanding of some of the types of questions to ask in this investigation (though every case is different according to the needs of the tenants) and a start on how to answer them. This guide may be useful to tenants outside Los Angeles, as the principles are quite similar across places– many cities have code enforcement agencies, and housing departments, and every place has an eviction court and property registry. Often you can access these resources in person if not online.

This guide does not direct tenants in things like the use of database software, spreadsheets, or Geographic Information Systems (GIS) that might make some of these tasks easier, though the technical demands are very basic. With a bit of googling and perhaps some AI assistance a tenant with very limited research experience should be easily able to do any of the tasks described. Free online Google tools like sheets and mymaps are sufficient for this.

This guide is far from exhaustive and there are many questions that might come up in the course of a campaign which can’t be answered here. The purpose of this guide is just to provide an inspiration and a start for tenants trying to understand their own landlords. Suffice to say, however, I have used the basic research procedure in many campaigns, and even to investigate my own landlord.

If you have feedback about how to improve this guide, please contact me! This is very much a living document, and has been updated as recently as 2024.

Good luck in your investigation, and in the struggle.

In Solidarity,

Alex

1. Finding Out Who Owns Your Building

Pretty much the most important information you can know as a tenant or a housing researcher is who really owns the property that you live or are organizing in. Given that this guide is intended for tenants, researchers at mostly non-profit housing organizations, and students, all of the resources we suggest you use to complete this research are freely accessible, except for the time they take to access.

Finding out who owns your building might be harder than expected. Many properties are managed by a company that acts on behalf of their owners, and interactions between tenants and building “owners” or building managers are often actually with employees of a third party management company.

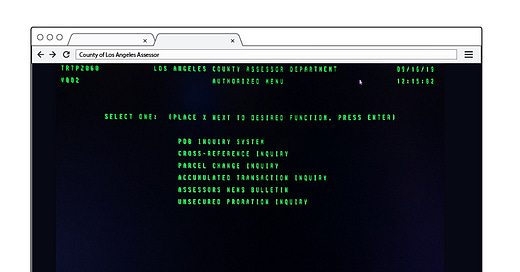

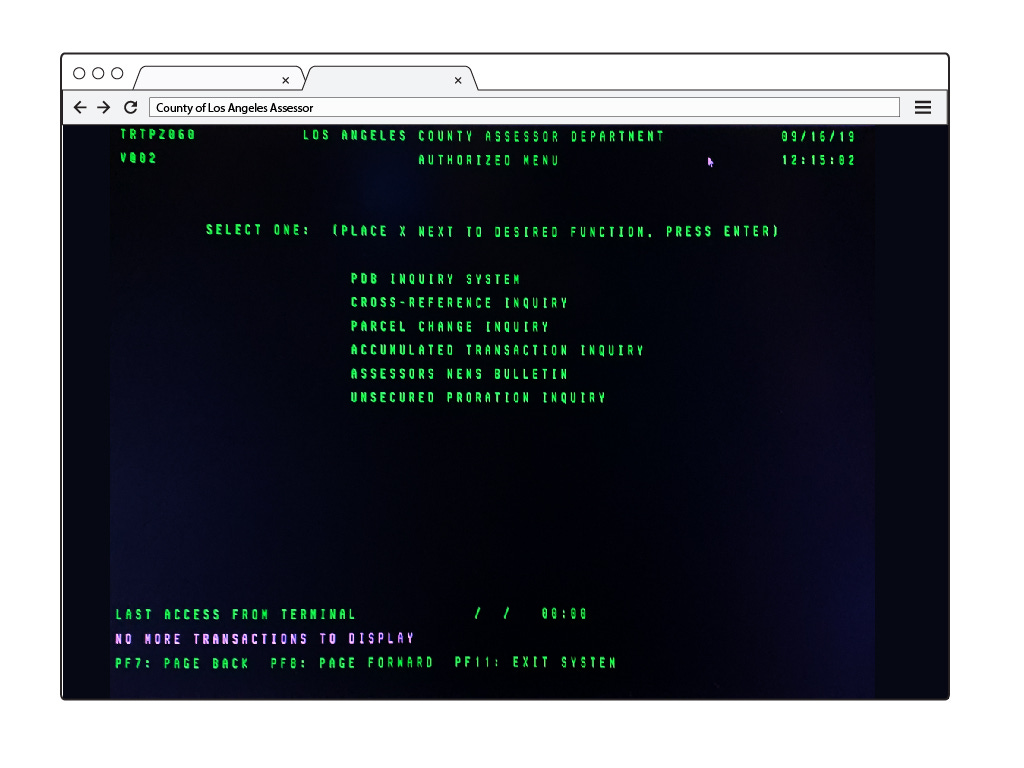

The best way to find out the owner of your property is by using the Los Angeles County Assessor’s property database. Accessing the ownership information through the assessor is one of the few free resources to obtain this information, provided you are willing to make a trip to Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration at 500 W Temple St, Los Angeles, CA 90012, to visit their public counter in Room 225. There, you will be able to use a public terminal to access the assessor database and search for properties through the PDB Inquiry System, as shown in the image below.

Though the interface is clunky and not easy to use, it provides a ton of important information. The assessor rolls provide the APN or Assessor Parcel Number of a property which is important for accessing other information through city and county data portals. They also show the name of the entity that owns the property, and you can search that name to find out other properties the landlord owns by their APN. You can also remotely access the data through the assessor’s website though there is a price per search.

If your organization has access to SAJE’s OWN-IT! tool, then accessing ownership information through the assessor is much easier, just enter the address of the property into OWN-IT! and the information will be brought up immediately.

OWN-IT! is still very useful if you have not received login access to the site. The public version, as shown above, still provides information linking all properties with the same owner by mailing address, exportable as a csv file, which can save you a great deal of time searching through the assessor terminal and compiling addresses from there if you already know the owner name. OWNI-IT! also visualizes the linked properties through its mapping interface which allows you to see how the landlord’s properties are spread across the city, and provides in an easily accessible format the address in addition to the APN.

2. Finding Out Who Really Owns Your Building If You Have a Corporate Landlord

After completing the first step in this research guide, you may be shocked to find out that your landlord is not a person, but actually a corporate entity like a LLC, a Trust, a LP, or a holdings company for example. Given that about 40% of all residential property, and 53% of all multifamily properties in the city of Los Angeles are owned by corporate entities instead of individuals this is extremely likely.

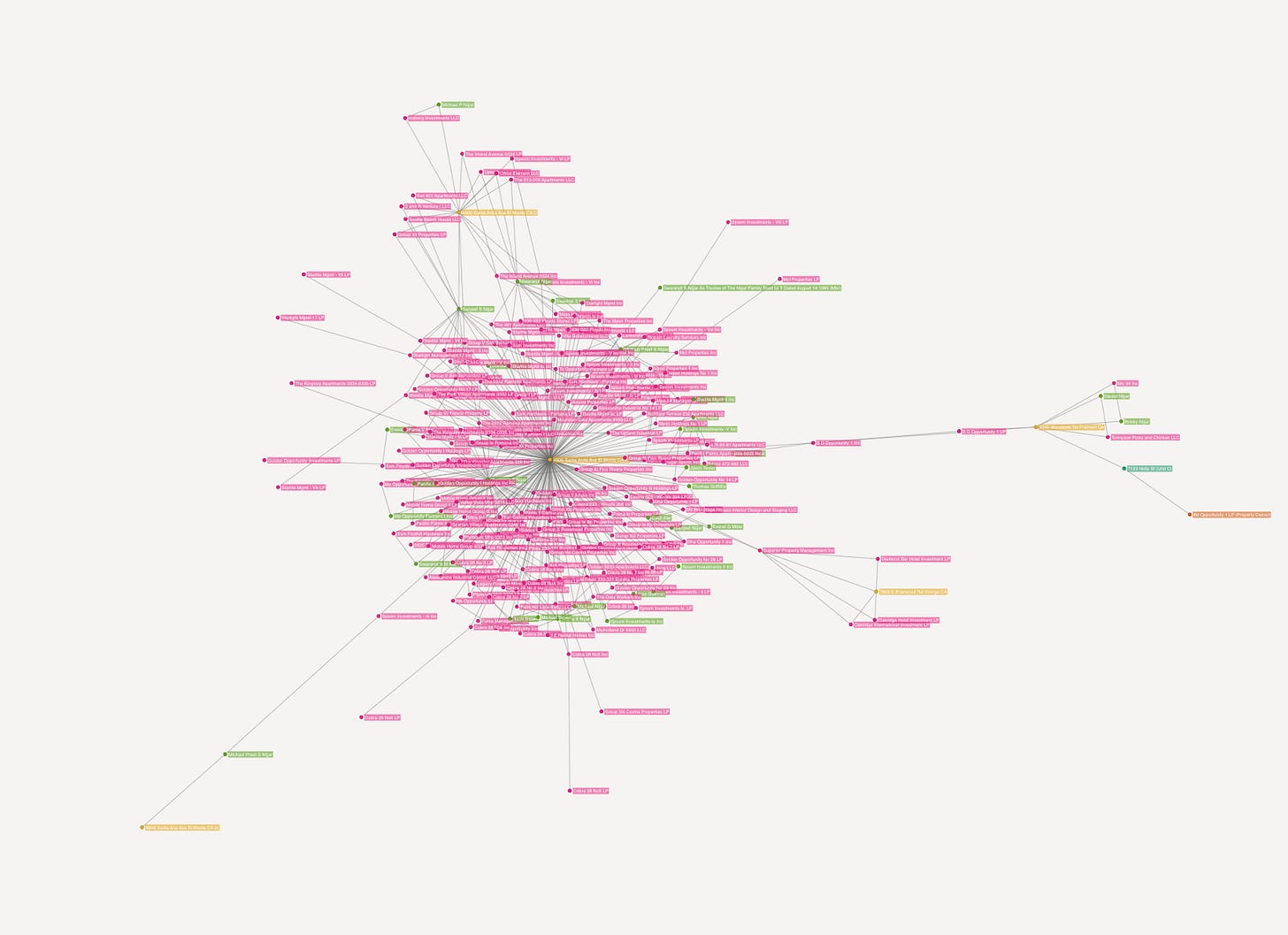

After completing the first steps you should have at least two pieces of information that will help you investigate a corporate landlord. First, you should have a name for the company- which could be much less useful than one would think given the ease of creating shell companies and their widespread use by property owners. You should also have the mailing address of the landlord. With these two pieces of information, the next step is to start searching for corporate records. Corporationwiki, and OpenCorporates are good places to start looking for information and can reveal links between companies, as well as who their owner or manager is.

The most important documents that are accessible on corporations are their registration and statement of interest forms, which are filed with the California Secretary of State. Both of these documents are downloadable through an online search tool, and often contain the name of the owner or managing entity of the corporation. If the landlord owns property in California, you can use the Evictorbook lookup tool to find networks of associated businesses to check records for regardless of whether the landlord owns in the Bay Area cities covered by evictorbook.

In some cases, the company may be owned by another company, or registered under a corporation service entity intended to shield the owner’s identity from the public and the government. This is called a shell company, and many unscrupulous investors use a plethora of them to hide their interest.

Searching for information based on the address of the company can also yield results. Often, a shell company shares an address with the company that owns it and by looking up the property owner for that address, or even by using google you can find out what other businesses are located there.

Shell companies often also use P.O. Boxes to further hide their identity. In California, however, you can find out the owner of any P.O. Box that is used for a business by going to the Post Office with evidence a business is using the P.O. Box, like property records, or corporate filings. This is another way to find out the true controlling entity of a shell corporation.

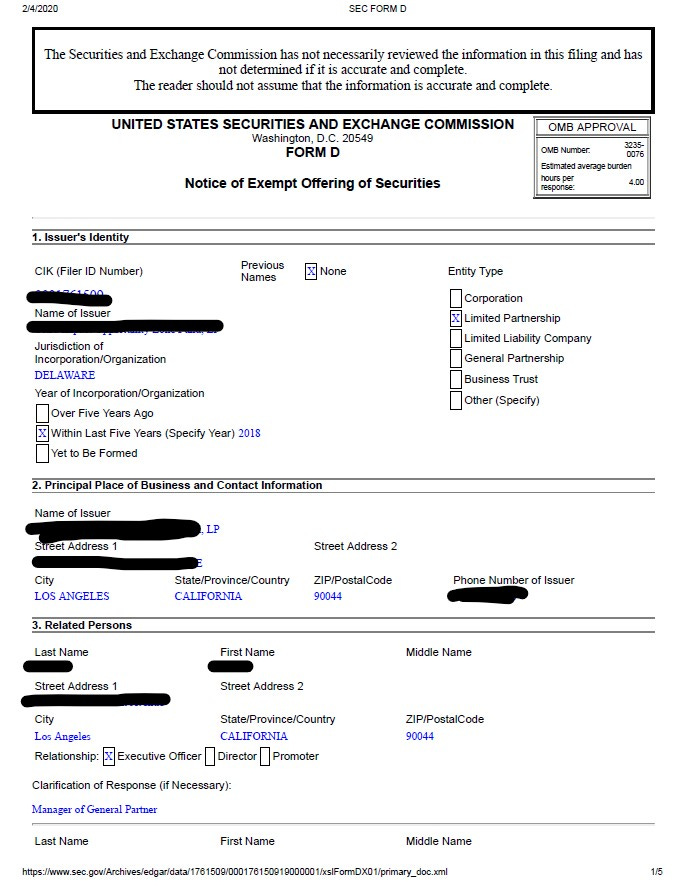

If your landlord is a major private equity company with publicly traded funds, or publicly traded corporation, or publicly issues securities (stocks, bonds, and debt backed by assets), you should be able to obtain more information about the financial situation of the company by using the Security and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) public data portal EDGAR. Please note that EDGAR has several search tools, and you may want to start with the company and mutual fund search bars, before moving on to a full text search. A copy of a SEC form D filing is reproduced below.

There are several useful SEC filings that larger companies are required to make, including the 10-K annual report which contains a wealth of information for companies that file them. Form DEF-14A also contains a lot of information about the executive structure of a publicly listed entity if available. Unfortunately, many private equity companies, which make up the bulk of corporate property owners, are not publicly listed and are therefore not required to make SEC filings, or are only required to make SEC filings for certain parts of their holdings.

One more approach is available for researchers desiring more comprehensive information on a larger company, which is to find out what local universities have Lexis-Nexis Academic and visit their library for access to the service. Lexis-Nexis Academic provides both a Public Records search feature that can turn up more property information, as well as the ability to generate a company profile through a service called Company Dossier.

Finally, visiting the website of the company you are researching should not be skipped. Company websites can sometimes provide a ton of information about the company’s structure, executives, investors, partners and holdings. In some cases this information may be publicly accessible, in other cases it may be behind a login or otherwise not accessible through the public webpage, but if you notice a common pattern in the company’s extension names (like theoreticalcomapny.com/property/1234)) you can try and use the URL bar to poke around for similarly named pages (like theoreticalcomapny.com/property/5678 for example).

3. Researching Your Landlord’s Practices Using Public Data

Now that you have some idea of who owns your building, and a list of addresses for the other properties that they own, you can start to get a picture of what kind of issues are happening at their properties.

Broadly speaking there are a few types of landlord practices that you can get information on through public data, with varying levels of ease and clarity. In no particular order these are habitability/code violations issues, building and safety issues, evictions, legal disputes between landlords and tenants, other legal disputes resolving in a court case. One good place to start is with a free online public records search tool like those aggregated at Public Records Search Systems, or with the Lexis-Nexis tools described in the preceding section.

In the City of Los Angeles specifically there are several sources for the information you might want to obtain. Inspections, habitability complaints, and other healthy housing issues are typically the domain of the Los Angeles Housing Department (LAHD), which has an online lookup function for property information called the Property Activity Report (pictured below). For building and safety information, Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety (LADBS) has a web portal with a property search tool.

For Los Angeles County, there are similar resources. The Department of Public Health conducts multifamily building inspections and performs code enforcement, and has a property database and search tool accessible here. Los Angeles County Department of Public Works administers building and safety in Los Angeles County, and has an online property search tool as well.

All the data discussed thus far is available at the single property level, which is very useful in finding out everything about your building, but perhaps less useful in finding out about a landlord’s activities, unless you are prepared to go building by building through their portfolio. Luckily, many of these agencies provide jurisdiction wide data by address or APN, that you can compare to the properties owned by your landlord. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health provides a downloadable dataset of all inspections and complaints through the county open data portal. The city’s Department of Building and Safety also has a regularly updated online dataset, available through the City of LA’s geohub. It is also possible to use the California Public Records Act to obtain records on a set of properties by APN or address from LAHD or LA County Department of Public Works, though this takes some time to receive in response.

It is worth noting that using APNs is the best practice for associating properties with other information like complaints or inspections, because the addresses may be inconsistently recorded between data sources. Therefore, when joining multiple datasets, always use the APN column for a table join in Excel or QGIS.

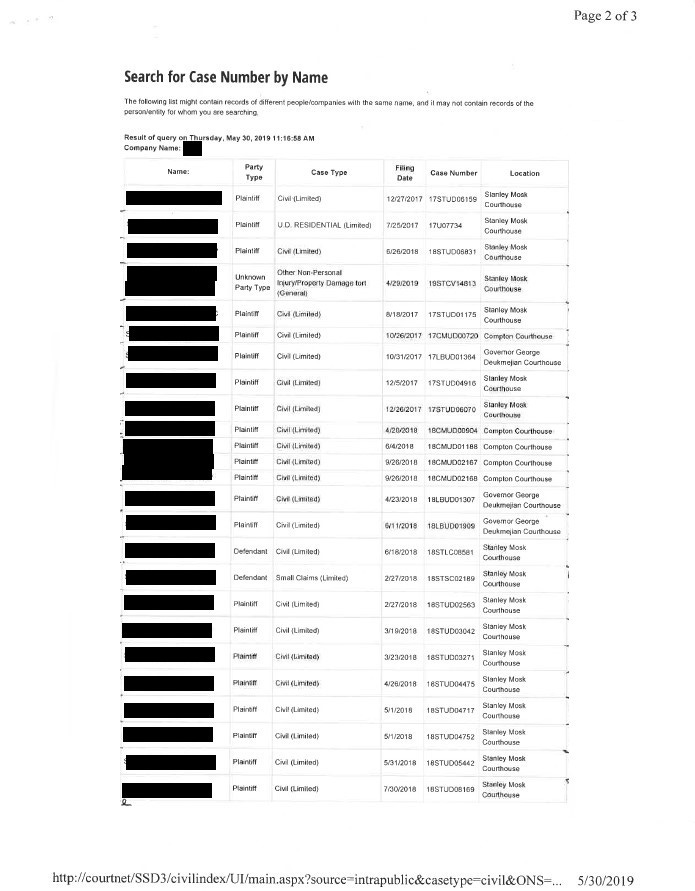

Another important source of information on a landlord’s practices, especially dealing with eviction, harassment, and severe landlord tenant relations issues or habitability issues is the County court system. The best way to access such records is to go to Stanley Mosk Courthouse (111 S Hill St, Los Angeles, CA 90012) and use the records lookup computers that are publicly available to search for case files by the name of the entity you are interested in. This function is also available through the internet but there is a cost per search.

Court records can contain information on civil lawsuits, labor disputes, small claims from non-repair or destruction of property and other disputes, as well as eviction data. Evictions are not consistently categorized, appearing as either U.D. (unlawful detainer) Residential suits or Civil Suits, but can be identified by the presence of a “U” in their case number. Using the search by name function is effective in generating a list of case numbers for further investigation, but the records need to be opened to be able to find addresses for UD cases for example. One further issue specifically relevant to eviction filings is that many UD cases are sealed, and therefore inaccessible through any public records system, including the courthouse records. Still, courthouse records can provide a general picture of landlord misbehavior. It is important to keep in mind that the property may have separate management and ownership entities, and the management entity may be listed as the plaintiff or defendant in legal disputes involving the property.

Finally, LAHD collects data on uses of the Ellis Act (a state-wide law that allows the no fault eviction of all tenants in a building, circumventing just cause protections), and Cash For Keys transactions in the City of Los Angeles. These are both tactics used by landlords to displace tenants from buildings that they want to use in a different manner, and are related to gentrification. A dataset on this information including APNs, and addresses is obtainable through a Public Records Act request.

Since 2023, LAHD also maintains a record of all eviction notices filed with the agency. While these records do not include the landlord's name, they do include the APN and address of the property which you can match to the landlord's portfolio using a table join, identically to the code enforcement records.

4. Basic Revenue and Portfolio Financial Estimates

Due to the lack of disclosure requirements for business entities in the United States, the revenue landlords receive from rents is not public record. While there is a gross receipts tax in Los Angeles that would illuminate this question, those records are not legally able to be disclosed to the public by tax collecting agencies under current law. Similarly, while the largest, publicly traded companies will release substantial financial records as a result of their public issuance of securities and the requirements imposed by federal regulators for those entities, most landlords, as noted above, are not publicly traded. If limited information about a landlord's finances is available from the sources above, it may be desirable to make a rough estimate of their revenue and portfolio value based on property information.

There are a variety of ways in which this can be accomplished. Property data from the assessor offers reliable information about building size, unit counts, and built year, and less reliable information about purchase price and assessed value. While it is possible to simply aggregate assessed value across a portfolio as recorded by the assessor, this is not a reliable strategy for generating accurate estimates of the value of a landlord’s holdings, because the particularities of CA tax law due to Prop 13 all but ensure this will be a considerable under-estimate, especially if the landlord has owned properties for a long time. This is because the assessment of properties occurs once at sale, and then is adjusted based on a formula that does not reflect anything resembling current market value over passing years. Similarly, it is possible to aggregate sales values, and adjunct for inflation using the purchase year of the structure, but the recording of sale dates and values is inconsistent, making this prone to error.

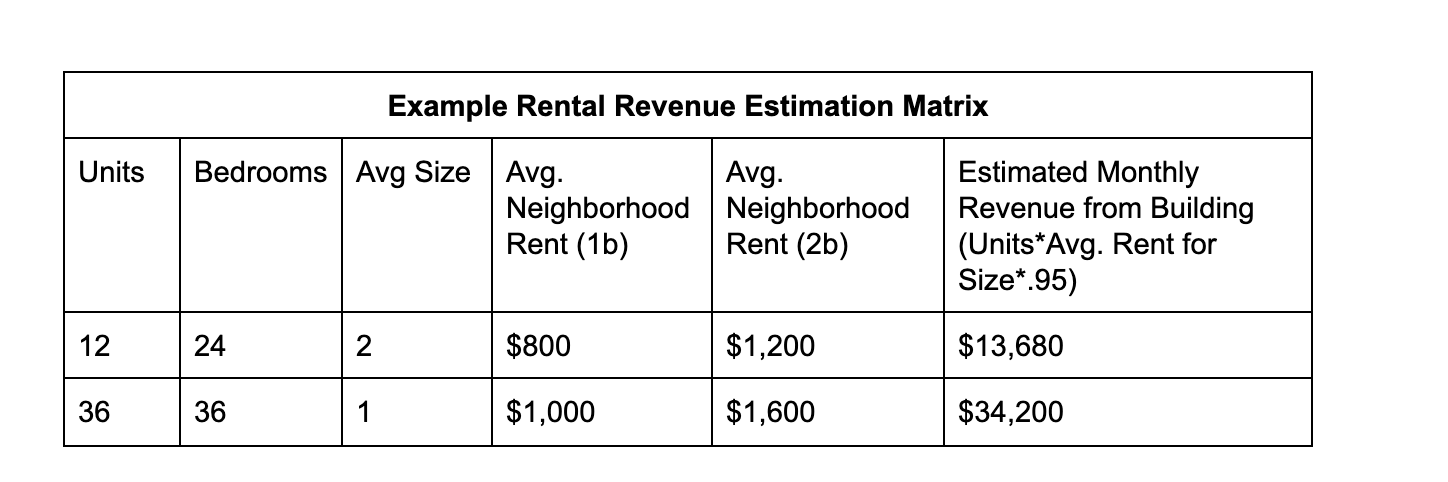

Estimating rents and portfolio value from the property characteristics is sufficiently accurate and far more reliable than using the aforementioned approaches. There are many ways to accomplish this, and it is not necessary to use overly sophisticated methods. Estimation of rents is more straightforward. Given the characteristics of the structures (bedrooms vs. units), and the average rents in the area in which they are located (eg. Zillow data, ACS data from the U.S. Census Bureau), a basic estimate can be easily derived. For example, a portfolio of 700 units, averaging 2 bedrooms per unit in size, concentrated in one neighborhood, can be estimated at 665 times the average rent for a 2 bedroom apartment in that neighborhood, allowing for 5% vacancy. If multiple neighborhoods and building types are involved, using GIS can make this process much easier, though any tabular data processing software will work fine as illustrated below.

Estimating portfolio value is a similar process. Using available property value datasets (ACS data from the U.S. Census Bureau, or the FHFA’s land price index dataset) to obtain a measure of average value per square foot for the areas in which the landlord’s properties are located. Given this value, it is easy to multiply the size of each building in the landlord’s portfolio by the value per sqft measurement, using Assessor’s information, then find the sum of all properties. A subsequent example matrix can be found below.

In both cases, these methods provide extremely rough estimates of the landlord’s revenue and holdings, but each is accomplishable with little background in financial analysis and easy to complete with any software suitable for tabular data. Most important in many cases is to get a basic understanding of the landlord’s size and revenue, as well as to identify properties that may have an outsized importance to them.

5. Identifying Priorities for Organizing

Once you have various layers of information about the state of buildings owned by your landlord, you can begin to identify which buildings should be priorities for outreach and organizing. The most important layers that will be available for all landlord’s properties are the building characteristics (units, building age, etc.) provided in the case of LA by the Assessor’s property data, code enforcement information, and evictions information. The creation of a priority index, as shown below can help rank a landlord’s many buildings and provide easily visualizable and understandable information to assist in the targeting of properties for an organizing campaign.

Organizers ultimately should be determining the priorities by which properties are ranked, and the list in the sample index is not at all comprehensive. These metrics are a good base, however, as they capture a range of concerns about building conditions and allow for organizers to define areas of particular interest to prioritize. Large buildings are also often more efficient because it is easier to cultivate a larger tenant leadership base if there are more tenants in the building.

Mapping the priority index is also useful, because it helps identify clusters of buildings that may make sense for organizers to target by convenience, even if not all of the buildings are the highest priority. It also allows a researcher to overlay relevant political or administrative boundaries (Is the property in the city or unincorporated? Is the property in Council District X or Y? Which elected body or code enforcement apparatus will be most receptive to tenants demands and priorities? These are all relevant explorations of this theme.), or other specific geographies of interest that represent special overlay zones, neighborhoods or historic/cultural communities, or even demographic and socioeconomic data.

It’s important to keep in mind, however, that this priority index is only a starting point. Throughout an organizing campaign, escalating landlord behavior, worsening building conditions and shifting political alignments may necessitate a remapping of the canvassing priorities. The concept of indexing priorities is highly flexible, and new categories can be added as needs evolve. One particularly relevant category is the existence of strong leaders already cultivated within a building.

Another consideration for tenant organizers working within a specific neighborhood is the importance or necessity of organizing outside of the neighborhood. One way to conduct a power analysis that can help speak to this is by evaluating what proportion of the landlord's revenue comes from your neighborhood. The following image shows one way to do this kind of analysis.

To make such a graph, using your list of the landlords properties and revenue estimates, you can group the properties by zip code and sum the revenue estimates for each. From there you can compare each zip code (or sets of zip codes) to the landlord's total revenue, and thereby find out the relative importance of each place for their revenue.

The graph displayed contains a point for each and every landlord in Boyle Heights for example, but the principle is the same: the higher the proportion of estimated revenue that comes from a place, the more important it is to the landlords bottom line.

If a small share of the landlord's revenue comes from your neighborhood, it might be prudent to reach out to other organizations or plan to canvas other areas.

6. Landlord Lobbying and Political Activities

Now that you have an understanding of who your landlord is and what their practices are, it is useful to know what their political activities are, and who their friends in power may be. The usefulness of google cannot be overstated here, and several media outlets like curbed, urbanize, the real deal, and bisnow, which are good resources generally, report fairly expansively on the activities and connections of real estate players.

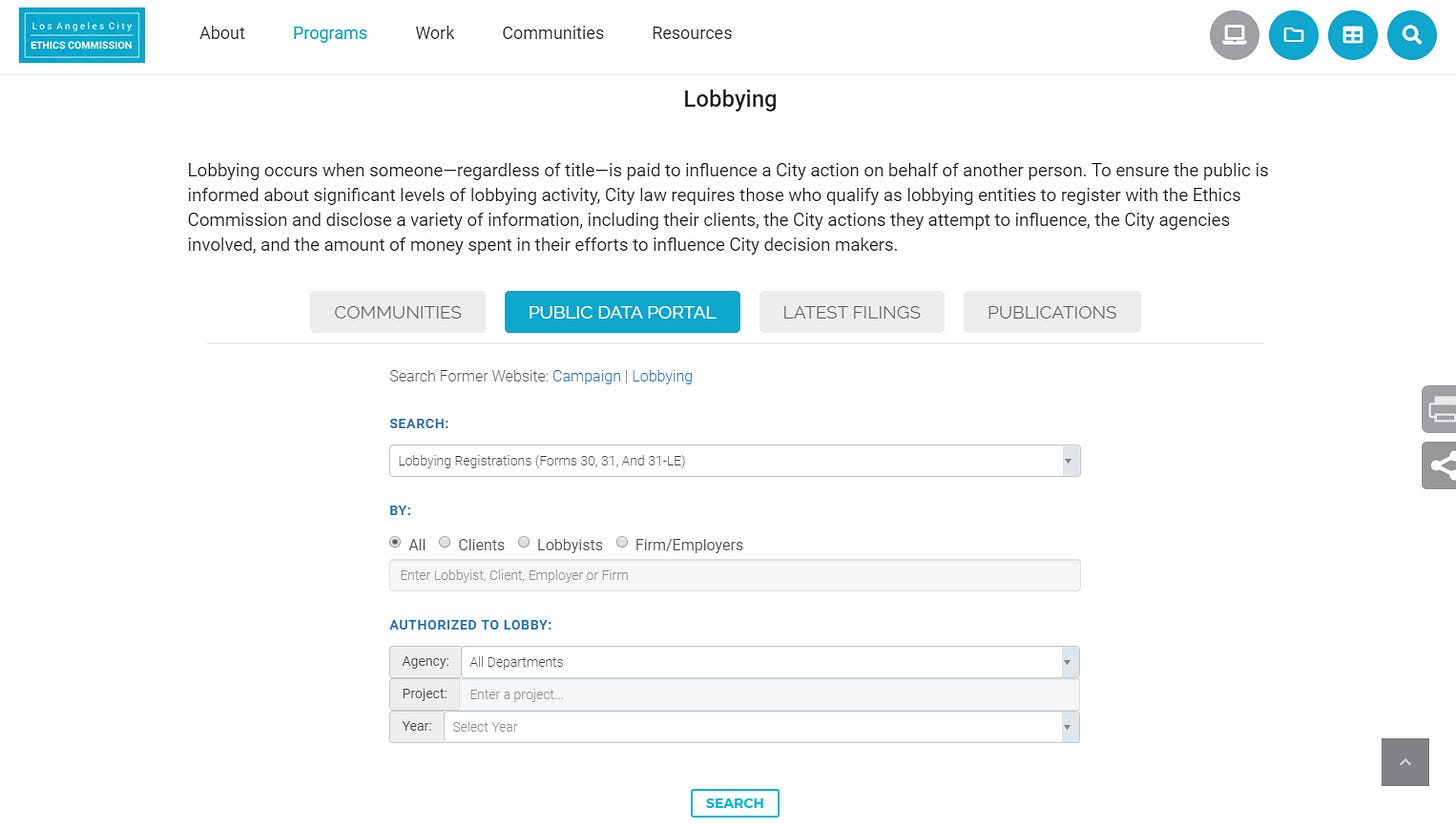

Specific information on the political contributions and lobbying activities of persons and businesses within the City of Los Angeles is available through the city’s excellent ethics portal. Finding information at the statewide level is harder, though there are several online databases that collect donor information, and the state Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC) allows the download of candidate’s donor information through their website, though it does not have a donor search function. The FPPC also responds to public records requests. Information about spending on ballot measures is available from some of the links above, notably FollowTheMoney.org. FollowTheMoney and OpenSecrets are also great resources for finding out if your landlord has donated to any national political figures like presidential candidates, for example, or congressional campaigns.

The council file management system, linked above in section 2, can also provide some insight into your landlord’s lobbying activities. Searching the landlord’s name in the ordinance section can turn up any comments on legislation the landlord has made that are read into the public record.

Your landlord may also be active through a proxy organization like the Apartment Association of Greater Los Angeles (AAGLA), Central City Association of Los Angeles (CCALA), the California Association of Realtors (CAR), and the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. Many of these organizations have some information as to their constituents on their websites. AAGLA’s board of directors can be found here, CCLA has an online directory, as does The LA Chamber of Commerce. Google, especially advanced search functions, can also be useful in figuring out if your landlord is involved in any of these activities. As non-profit organizations, CCLA, CAR, and AAGLA may be required to disclose their funding sources through their tax filing, called a form 990, which you may be able to find through a Guidestar search. Beyond professional associations, your landlord may also be affiliated with philanthropic foundations, or civic organizations, sitting on the board of a charity, or hospital, or having some connection to a university, for example. The best way to find this type of information is typically through google, but a ton of information on the practices of your landlord can sometimes be found in media sources. Sources like LexisNexis Academic, and ProQuest, available through a university library provide historical databases of newspaper filings, but a far larger archive is available online here at newspapers.com.

7. What’s Important and What’s Not

Every landlord is different and the difficulty of researching them can vary immensely depending on the type of entity, the size, and the publicity level of the landlord. This makes it important to prioritize information that answers the following questions:

Who are the key players and what are the most important relationships within this entity?

What are the behaviors and practices that make this landlord problematic?

How does the landlord treat their tenants?

What are their liabilities and weaknesses?

Ultimately, the most important objective of your investigation is to paint a general picture of your landlord’s strategy, and uncover the most effective ways of contesting it. This overall picture is far more important than any particular piece of information discussed in this guide and often, much of that information will not be available for any given landlord. It is important not to get discouraged by lack of progress on one point, or to get bogged down pursuing one productive area of research to its ultimate conclusion.